25 Nov Rubrics

You know that feeling that the rubric you have created is actually inadequate when you are assessing? You want to be as objective as possible and stick to the descriptions formulated as much as possible. But because, for example, the structure of the text in the assignment is not correct, actually the argumentation cannot be followed either. Structure and argumentation are two separate items in the rubric. Should you now score them both low? Perhaps you had agreed during discussions with colleagues that you wouldn’t, but this feels wrong. We have news for you: there is a science-based, reliable alternative to rubrics.

What is a rubric?

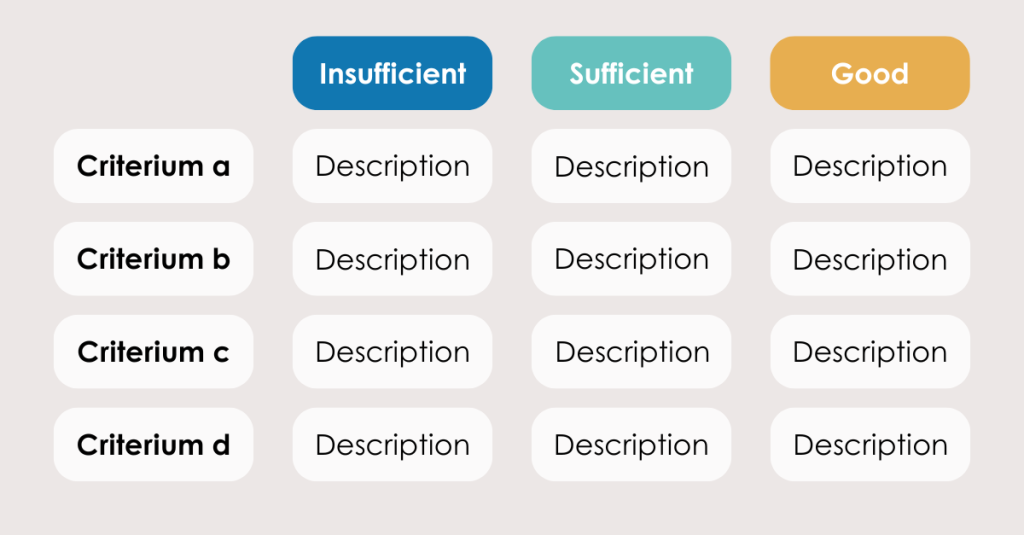

A rubric names the criteria that students’ work must meet, including a description of the different levels of quality and a form of scoring¹,². This definition sounds logical, but be aware that we only talk about a rubric when all these elements are present. So if you have made a criteria list with a scale from 1 to 5, you do not officially have a rubric yet because a description is still missing.

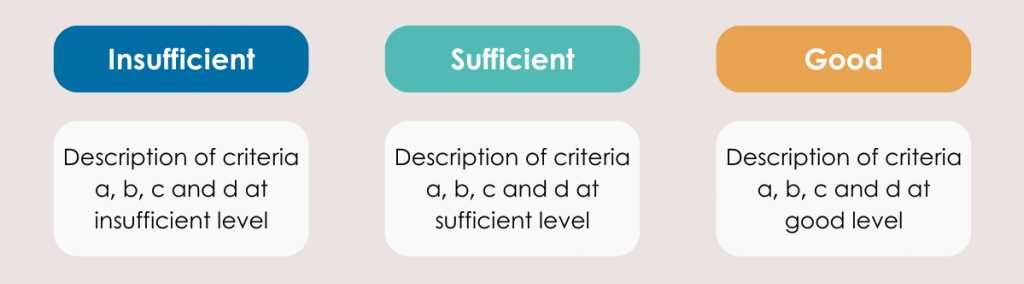

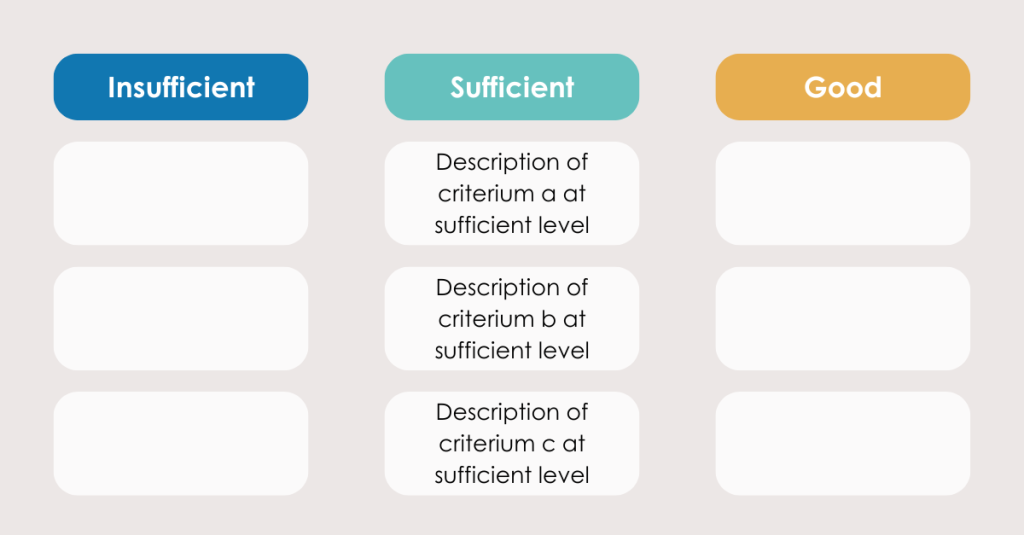

Rubrics can take different forms. A more analytical rubric (figure 1) will describe in detail what is expected per criterion. A holistic rubric (figure 2) leaves more room for interpretation by naming several criteria in one description. An analytical rubric is useful for formative purposes, because in that case you immediately get detailed feedback broken down per criterion¹,². At the same time, a holistic rubric leaves more room for interpretation and avoids an artificial division of a complex task. After all, criteria are often linked, for example when it comes to argumentation and structure of a text. An intermediate form is the use of a single point rubric (Figure 3): it describes criteria at one level, but with the idea that further information is filled in by the teacher or peer. This leaves more room for own interpretation and explanation while still breaking down information per criterion.

The advantages

There are several advantages to using rubrics. When used for summative assessment, they can contribute to the validity and reliability of exams or tests. They also help create transparency among students¹. Test expectations become clearer. Clear expectations ensure that self-efficacy (belief in one’s own abilities) can be promoted. In addition, such clarity helps the feedback process, reduces nerves and promotes self-regulation³.

The disadvantages

At the same time, there are drawbacks to using rubrics. First, making a good rubric is quite difficult and takes time. The literature on rubrics shows that the words you choose make a lot of difference to the effectiveness of rubrics¹. Your rubric should focus on descriptive language, not evaluative language. For example, if you put in a rubric that there should be a good structure in the text, what do you mean? Rather, change that text as follows: ‘the design, results and discussion are described and follow each other logically’. There is, of course, still some room for interpretation, because what do we mean by logical? To ensure that everyone understands what is meant, it is therefore important to discuss the descriptions, or (even better) formulate them together¹,³.

The above immediately leads to the second drawback: the effectiveness of rubrics is rather dependent on how they are used. For formative application, rubrics are often too abstract for students to understand properly. So you have to have time to discuss the rubric and make it understandable for students⁴.

For summative purposes, rubrics are often more complicated to deploy than traditional criteria lists¹. After all, is there enough room to formulate a well-thought-out rubric together with colleagues? And without proper consultation with colleagues, will you achieve that improvement in the reliability and validity of your evaluation, that was the goal of using a rubric in the first place? In spite of all the good intentions, practice often turns out to be obstinate². For teachers, rubrics sometimes feel like an artificial division of a skill into parts that are very similar. Without clear agreements, there is a risk that a rubric will not be used as intended.

Formative, summative, comparative

Researchers seem to reasonably agree that rubrics are best used to promote student learning¹,⁵,⁶. This while teachers continue to see rubrics primarily as an assessment form. Essentially, an effective rubric is used as a tool to provide clarity to students and further the feedback process. But if students want to use this tool effectively, then you also pay attention to explaining your rubric. This can be done very well by having students assess comparatively⁴.

In comparative judgement, you compare (example) works with each other. Simply sharing examples does not work to get quality standards clear, you have to actively work with them. Comparing and discussing different (example) works promotes quality awareness among students⁴. This works well with Comproved’s comparing tool. After comparing, you and your students can make or adapt a rubric in which you make explicit what the characteristics of a well-executed assignment are. This way, criteria and descriptions become concrete. During a peer assessment, students can then use the rubric as a tool to formulate peer feedback.

For summative assessment, comparative judgement is a very good alternative to using a rubric. This is because comparing work is a much more natural and reliable process than working with criteria. With comparative judgement you no longer divide a complex skill into artificial parts, but assess holistically based on the expertise of several assessors simultaneously. This method proves reliable and valid, according to several years of research⁷,⁸. In Comproved, you easily organise an assessment with which you assess comparatively. Want to know more? Read on for other people’s experiences!

Literature

1Brookhart S. M. (2018). Appropriate criteria: Key to effective rubrics. Frontiers in Education, 3, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00022

2Ragupathi, K., & Lee, A. (2020). Beyond fairness and consistency in grading: The role of rubrics in higher education. In C. S. Sanger and N. W. Gleason (eds.), Diversity and Inclusion in Global Higher Education, (pp. 87-109). Palgrave Macmillan https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1628-3_3

3Panadero, E., & Jonsson, A. (2013). The use of scoring rubrics for formative assessment purposes revisited: A review. Educational Research Review, 9, 129-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002

4Bouwer, R., Lesterhuis, M., Bonne, P., & De Maeyer, S. (2018). Applying criteria to examples or learning by comparison: effects on students’ evaluative judgment and performance in writing. Frontiers in Education (3), 86. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00086

5Reddy, Y., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35, 435–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930902862859

6Panadero, E., & Jonsson, A. (2020). A critical review of the arguments against the use of rubrics, Educational Research Review, 30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100329

7Verhavert, S., Bouwer, R., Donche, V., & De Maeyer, S. (2019). A meta-analysis on the reliability of comparative judgement. Assessment in Education: Principles, policy & practice, 26(5), 541-562. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2019.1602027

8Lesterhuis, M., Bouwer, R., van Daal, T., Donche, V., & De Maeyer, S. (2022). Validity of comparative judgement scores: how assessors evaluate aspects of text quality when comparing argumentative texts. Frontiers in Education, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.823895