18 Mar Feedback literacy

Your feedback process is solid. You have created good opportunities for your students to use feedback to improve their work. Now it is also up to the student to make use of all those opportunities. Students could learn so much, but are they open to receive feedback? Do they take feedback from peers seriously? And do they manage to take a good next step in response to the feedback? Chances are there is still some work to be done. The concept of feedback literacy can help.

What is feedback literacy?

Feedback is a process in which both the student and the teacher play a role. For this process to work well, you will need to be able to read, interpret and use feedback properly. This applies to both students and teachers. For students, feedback literacy is defined as the insights, abilities and states of mind (dispositions) needed to understand information and use it to improve work or learning strategies¹.

It is also important for teachers to be feedback literate, but the definition for teachers is slightly more comprehensive. Teachers will need to be able to shape the feedback process effectively at different levels (from teaching design to student interaction)². This may sound rather complicated. So how do you do this? To come to an answer to this question, we first dive into feedback literacy for students, then we look at feedback literacy in teachers. We then provide concrete tips for promoting feedback literacy.

Feedback literacy for students

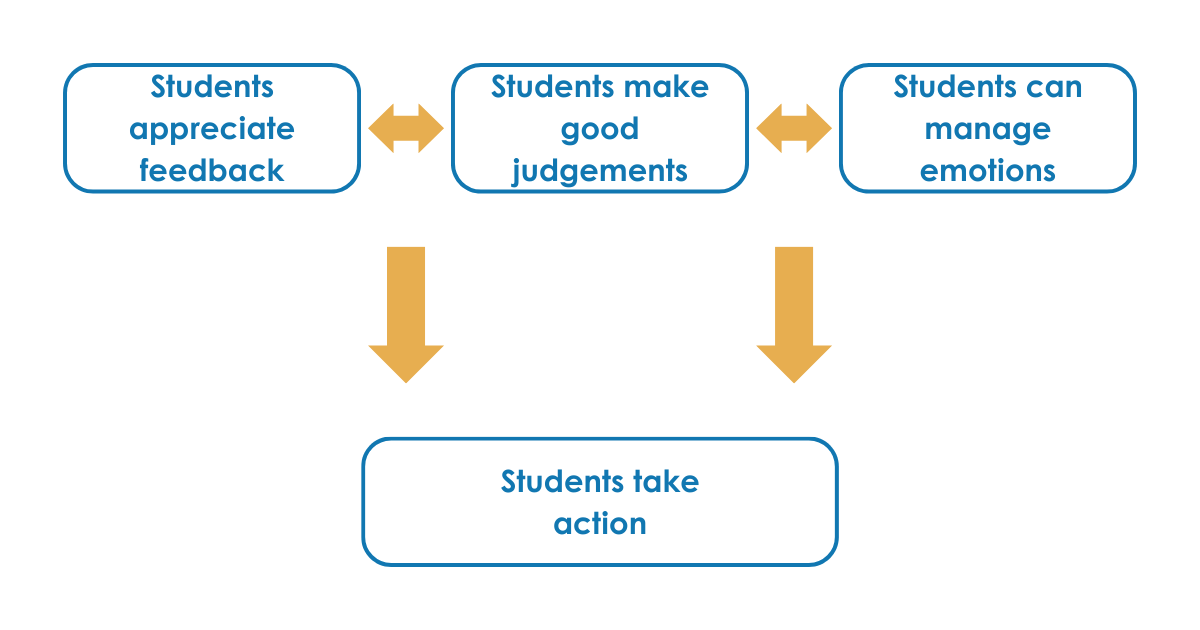

There are several descriptions in the literature of traits that feedback literate students are said to possess¹,⁵. The best-known description breaks down feedback literacy in students into the following four elements¹:

- Students value feedback: students understand and value feedback and recognise that they have an active role in the feedback process. They understand that feedback can take different forms.

- Students make good judgements: students develop the capacity to make good judgements about the quality of their own work and that of others.

- Students can deal with emotion: students do not become defensive in the face of critical feedback and have the courage to proactively ask for feedback in order to keep improving themselves.

- Students take action: students develop strategies to actively engage with feedback.

Figure 1: the four elements of feedback literacy

How are you a good example of feedback literacy?

So what about feedback literacy among teachers? The first thing to conclude is that teachers must also demonstrate the above behaviours in their own feedback practice⁶. How else can you expect students to develop feedback literacy? If you yourself are still ‘stuck’ in the idea that feedback is something you give to a student and that’s the end of the matter, it obviously becomes difficult to teach students that feedback is a process in which they too have a part. Or if you yourself react defensively to feedback from students, can you expect them to be open to your feedback?

A little more is expected from teachers than setting a good example; after all, they also design education. Based on research, a nice list of competences is mentioned that teachers should possess to be able to develop feedback literacy well². A distinction is made between the macro level, in which you work on feedback literacy across disciplines, and the micro level, in which you formulate individual feedback correctly. For the full list, please refer to the study itself² and this blog article (in dutch).

The list of competences is derived from various studies on good feedback practices and the activities teachers carry out in them. So it is also not necessarily said that one teacher should have all these competences, as long as you can work together to create an environment that promotes feedback literacy.

Stimulate feedback literacy

All well and good, but this is quite a list of things to consider. So how do you do all this on a very practical level? The honest answer is that it is not all that clear yet⁶. It turns out that developing feedback literacy is context-dependent and so there is no single recipe for shaping the process properly⁷. When it comes to educational design, the following principles are at least seen as important⁷:

- Provide an intentional design in which you ensure that students can go through the entire feedback process. We will soon publish an article on what an effective feedback process looks like;

- Make sure students can practice giving and receiving feedback in interaction enough. Practice makes you learn;

- Developing feedback literacy is ongoing. So also look at the development crosscurricularly. Pay attention to new contexts that may require additional learning, such as apprenticeships;

- Insight into students’ progression in terms of their feedback literacy is essential in order to match needs. Look for opportunities to monitor that progression.

Practical tools

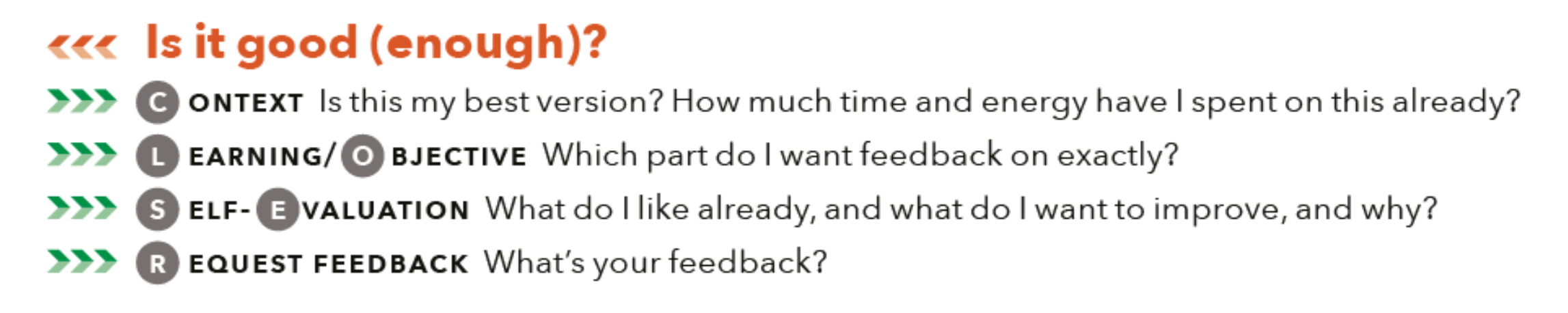

There are researchers who already offer more practical guidance. Specifically on promoting feedback literacy among students, concrete ideas can be found. For example, to support students in asking for feedback, an acronym for each type of feedback question has been devised to help students ask better questions⁸. Instead of asking ‘is this good’, encourage students to take their own role in the feedback process (see Figure 2). For more concrete tips like this, we recommend reading this article (in Dutch).

Figure 2: from the poster ‘Better ask for feedback‘

Other studies also share examples that deal with processing feedback information and taking action. A great example is feedback processing by having students create an action plan⁷. In an action plan, for example, students indicate what feedback they received, how they dealt with ambiguities or contradictions in the feedback, and what follow-up step they will take to improve their work.

Promoting feedback literacy with Comproved

Several features are built into Comproved to help promote student feedback literacy. For example, you can ensure that students ask a feedback question when submitting their work, to which all feedback providers can easily respond as they compare works. We have also built creating an action plan into the tool. Students create an action plan based on feedback from multiple peers and/or teachers. Students can use the action plan to further improve their work, and include the plan in a possible portfolio to show their development in feedback literacy. So with Comproved, we take part of the process off your hands. Want to know more about how this works? Read more here.

Disclaimer

Finally, an important note. Research on feedback literacy is relatively new. The concept seems to have been first mentioned in the literature in 2012, after which it has only really been widely published in recent years. Most studies still mainly focus on collecting experiences and developing models and theory. This is an important first step. Actually determining the influence of feedback literacy on, for instance, learning performance or motivation does not appear to be that easy, if only because (quantitative) instruments to measure feedback literacy have only recently been developed. In short: feedback literacy has a lot of potential to improve the feedback process, but keep reading critically when it comes to how exactly this should be done. Do the ideas fit within your own context? Given the great interest in the subject, there is no doubt that there will be many more practical tools to come.

Literature

¹Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

²Boud, D. & Dawson, P. (2023). What feedback literate teachers do: an empirically-derived competency framework. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48(2), 158-171. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1910928

³Nieminen, J. H., & Carless, D. (2023). Feedback literacy: A critical review of an emerging concept. Higher Education, 85, 1381-1400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00895-9

⁴Sutton, P. (2012). Conceptualizing feedback literacy: knowing, being, and acting, Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 49(1), 31-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2012.647781

⁵Molloy, E., Boud, D., & Henderson, M. (2020). Developing a learning-centred framework for feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(4), 527-540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955

⁶Little, T., Dawson, P., Boud, D., & Tai, J. (2024). Can students’ feedback literacy be improved? A scoping review of interventions. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(1), 39-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2177613

⁷Malecka, B., Boud, D., & Carless, D. (2022). Eliciting, processing and enacting feedback: mechanisms for embedding student feedback literacy within the curriculum. Teaching in Higher Education, 27(7), 908-922. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1754784

⁸De Kleijn, R. A. M. (2023). Supporting student and teacher feedback literacy: an instructional model for student feedback processes. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48(2), 186-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1967283