31 Oct Formulating specific learning objectives

Formulating learning objectives is seen as one of the most important tasks in shaping good teaching. Without learning objectives, there is no clarity about what is to be learned, what activities you perform in the classroom and how you then measure whether and what has been learned. How a learning objective is formulated is important. Research shows that specifically formulated learning objectives improve learning outcomes1. But formulating such specific learning objectives sounds easier than it is.

It is not entirely clear how learning objectives contribute to learning2. Several researchers offer opinions on what components a specific learning goal should consist of, what verbs to use and not use, and what levels of learning can be distinguished. Robert Mager (1962)1 distinguished between three basic elements of a learning objective and says that the performance, the conditions of the performance, and the level should be described. To describe the level, Bloom’s taxonomy is often used.

There are just a few problems with this way of working. Let’s take an example: the generic skill “academic writing” is concretized, among other things, by the learning objective “Students can write paragraphs that contain clear transitional sentences”. The learning objective is very specific and certainly gives students a more concrete idea of what is involved in academic writing. So what is happening?

Problem 1: We lose the overview

The more concrete a learning objective is formulated, the more it focuses on one aspect of a larger skill. In our example, the learning objective covers only a small part of academic writing. It couldn’t be otherwise, because otherwise the learning goal would no longer be specific. It would take an awful lot of learning objectives to describe academic writing in its entirety, and you would quickly lose the overview. As a result, both students and instructors may start to focus on only the learning objectives and no longer oversee the complexity of the entire skill. For example, in assessment, when a rubric seems to undesirably become a kind of checklist.

Problem 2: What exactly do we mean?

Specific learning objectives still need explanation. Teachers and students do not always know what a particular learning objective means and what is then expected of them3. For example, a student does not always know that in our example the verb “to write” is considered a high-order verb in Bloom’s taxonomy, and thus we expect something difficult. For instructional design purposes, it was certainly helpful to mention this verb, but does the same apply to communication with learners? Does “writing” even cover it, does the learner understand what we meant by it when we formulated the learning objective? And what do we really mean by ‘clear transitional sentences’? Reading a learning objective as a student often does not help to get a grip on expectations.

We give an alternative to make learning objectives specific: make an overview of the components that make up a skill and concretize with examples.

Step 1: overview

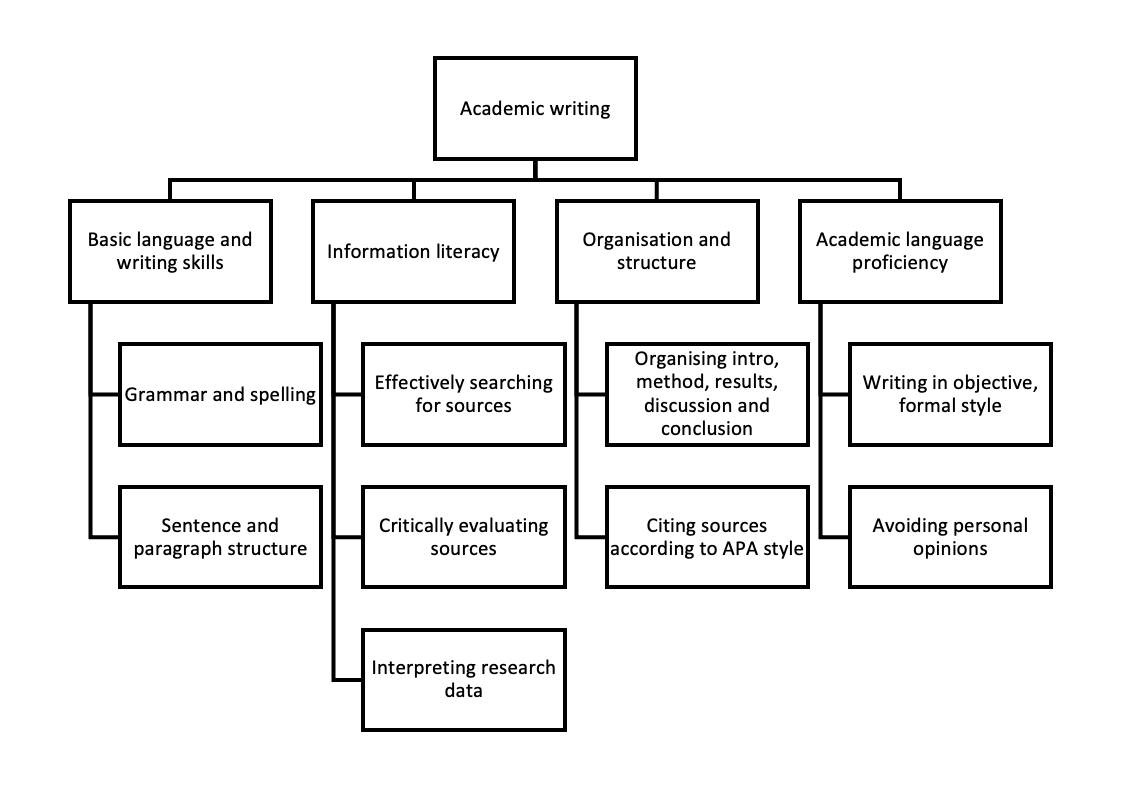

First, make an overview of the generic skill you want to teach. Instead of skill, you can also read competency, developmental objective or attainment target. In such an overview it becomes clear at a glance which parts a skill consists of. The overview also shows that the components are interrelated and are all needed to work on the skill. Such an overview could look like this for “academic writing”:

Step 2: Thinking about verbs

From skills, it may already be a little easier to think about exactly what you want to teach students. To do this, it may be helpful to think carefully about the verbs you use. As can also be seen in the hierarchy, there is a verb everywhere, such as “write,” “apply,” etc. Especially for design purposes, choosing the right verb is very useful to achieve constructive alignment. Thinking about verbs forces you to make design choices, so to speak: if you want students to actually be critical when searching for sources, it is important from the idea of constructive alignment that in your teaching you don’t just tell students how to do this. You will want to build in an assignment in which they will do their own critical searching.

Step 3: concretize with examples

To flesh out skills more specifically for your own situation, you can use examples. This also makes it clear to students what you want to teach them. For example, select three to five completed assignments from students from previous years, of varying levels. Compare these assignments with each other. You will see concrete examples showing how the level can vary. You can also have a conversation with each other about where the “bar” is set. Which examples are sufficient and which are not? What are exceptionally good examples and how can you tell?

It is most effective to have students do the comparing as well4. This way they also get an idea of the expectations for the assignment and can actively contribute their ideas. It also makes it clear to students that there are many ways to show a certain level: there is no one description that covers the load. You can summarize the findings of the comparison in an overview showing concrete examples of different levels.

But how do we assess?

Often learning objectives are the basis under assessment forms and rubrics. How do you still assess if you no longer formulate very specific learning objectives but base them on more generic skills with examples? If you use specific learning objectives to summatively assess a learner you run the risk of assessing in a fragmented way by trying to divide the skill into small parts. Often this does not work well because the different parts of the skill cannot simply be assessed separately. In order not to lose sight of the generic skill, you can work in the same way as when concretizing the level: compare! This way of working is the essence of comparative judgement. Want to know more about how to assess by comparison? Read more here.

1Marzano, R. J. (2009). Designing and teaching learning goals and objectives. Marzano Research Laboratory. https://books.google.nl/books?hl=en&lr=&id=BWoXBwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT15&dq=learning+goals+and+success+criteria&ots=_Z6qQ4MoXl&sig=M_WhhnxG5pDpPAMBpBd9azu9oyw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=learning%20goals%20and%20success%20criteria&f=false

2Kirschner, P. (2021). Leerdoelen: goal! Verkregen op 11-09-2023 via https://www.kirschnered.nl/2021/06/24/leerdoelen-goal/

3Mitchell, K. M. W. & Manzo, W. R. (2018). The purpose and perception of learning objectives. Journal of Political Science Education, 14(4), 456-472, https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2018.1433542.

4Nicol, D. (2021). The power of internal feedback: exploiting natural comparison processes. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(5), 756-778, https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1823314