06 Dec Validity

Good evaluation starts with validity, you learn as a teacher. At the same time, we often don’t know very well whether an exam or test is valid. How do you actually measure such a thing? We might create a test matrix to make sure we evaluate what we have taught, but validity is about more than just representing the lesson material in an exam or test. Are there other ways you can promote validity, and how do you do it? We explain exactly what validity is and how you can assess as validly as possible.

Whereas reliability is about the precision with which you assess, validity is about assessing correctly. Are you actually assessing the skill or knowledge you want to map, or are you assessing something else? Imagine, for instance, that you want to know whether a teacher in training is good at classroom management. You can present a multiple-choice exam, but does it say anything about how well the teacher in training can actually manage a class? If you evaluate validly, then you can actually use the exam or test for its intended purpose.

Different types of validity

If you browse the internet using the search term ‘validity’, you will often find a distinction between different types of validity¹. Think construct validity, criterion validity or content validity. While it can be useful to think about different types of validity, they actually always lead to arguments for or against one type of validity: construct validity². Michael Kane has written a lot about validity. He suggested that validity should no longer be seen as a concept that every teacher and researcher seeks evidence for in their own way. Instead, he argued that validity can be argued.

The following example shows how such an argument works³: a lawyer tries to convince a judge of a suspect’s innocence. The choice the judge makes depends on the quality and relevance of the arguments the lawyer presents, but also on the lawyer’s persuasiveness. All together makes the verdict, and it depends on the nature of the offence how much evidence is needed. Similarly, the same applies to determining validity. The greater the consequences of an exam or test for students, the more important it is to collect enough evidence for the validity of that exam. We can think of building a validity argument in the same way. We go to work as lawyers.

Step 1: use and claims

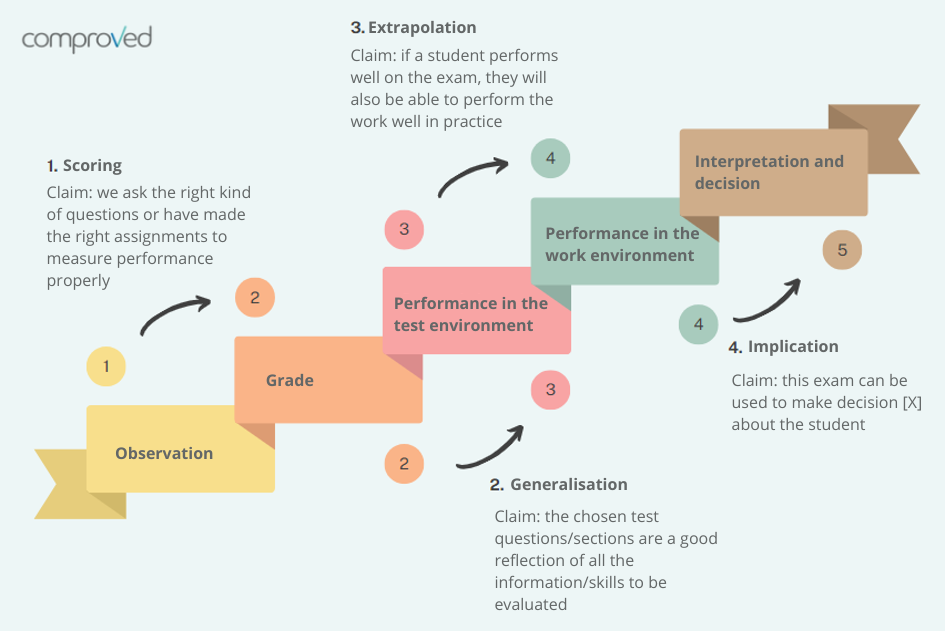

In the first step, you list the claims you expect to make with your exam or test. For example, to stay in the lawyer’s context, this involves the claim that the accused is innocent. An example of a claim aimed at evaluation is ‘a good score on the exam means that students can perform their work well’. The claims are initially about the observation you make during your exam and continue through to the decision you eventually make about the student based on that exam. See the image below for a concrete idea at what this means.

You will find that you may make claims that seem very logical to you. Still, it’s good to really explicitly name the claims you want to make. If you want to make a very important decision with the exam or test (such as whether a student will fail or pass), it is important that you gather enough argumentation that you can show that you can actually make such a decision based on your exam. The consequences are huge for students if something turns out to be wrong. This is different in a formative moment. So claims are different in every context in which you apply the exam. Ultimately, then, you are not determining the validity of an exam, but the validity of an exam in a particular context.

Step 2: evidence and arguments

The second step consists of gathering the necessary evidence to actually make your claims. You make sure, as it were, that your claims are also credible. The amount of evidence depends on the specific context of your exam: is it a high-stakes moment or not? In addition, you can think about the type of evidence, which often depends on the form of test you choose. A small list of possible evidence you can collect or generate per claim (See the article by Cook et al.³ for a more comprehensive overview):

1. Scoring

- Procedures for scoring the exam (e.g. rubrics, comparative assessment)

- Argumentation for choice of question type (e.g. open or closed question?)

- Explanation of assessor selection and training

2. Generalisation

- Test matrix with an overview of the number of questions per learning objective

- Report on consultation with teaching team on which questions to ask

- Explanation of how choices for assignments/questions were made

3. Extrapolation

- Needs analysis of the work context on what, according to professionals, needs to be learned

- Information on the level of agreement between subject experts on the value of the exam in practice

- Information about the consistency between the score on this exam and an exam with which you hope to evaluate roughly the same thing

4. Implication

- A reasoned choice of where to set the standard

- An eye for possible adjustments to the exam afterwards if necessary (delete questions, adjust the standard)

- An evaluation with students about the impact of the exam

And now?

Based on the claims and evidence, you can then make an argument about the validity of your exam or test. You certainly don’t need to have collected every possible form of evidence, as long as your argumentation is convincing for the claims you want to make. So choose the evidence that contributes a lot to your argument. Multiple types of evidence that complement each other (e.g. both qualitative information and ‘hard’ data) can also be a good way to strengthen your argument.

Often, in practice, you will find that the process of making claims and gathering evidence already greatly improves the validity of your exam. If you come across something in your exam that needs improvement, fix it as much as possible. In doing so, you make your argument for validity stronger and stronger. So conscious thinking is the most important step you can take.

Comparative judgement is valid assessment

Exams that measure complex skills sometimes raise some additional questions about validity. There is less often a right or wrong judgement to assess, and the judgement more often depends on the judgement of several teachers. Teachers differ in their focus when they assess a skill⁴. One might wonder how to arrive at a valid assessment then. In this case, comparative judgement can help.

Comparative judgement ensures reliable scoring of your exam by starting from the intuitive process of comparing works. Assessing holistically allows more generalisation across tasks. In addition, assessors no longer have to adapt to rubrics and instead their expertise is used as a force for valid assessment. Indeed, to measure a good representation of a complex skill, multiple assessors are actually necessary⁴. All these advantages translate into strong arguments for making your validity claim. Wondering how comparative judgement works? Read on here!

Literature

¹American Psychological Association (2023). APA dictionary of psychology. Verkregen via https://dictionary.apa.org/criterion-validity

²Kane, M. (2004). Certification testing as an illustration of argument-based validation. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives, 2(3), 135-170. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15366359mea0203_1

³Cook, D. A., Brydges, R., Ginsburg, S., & Hatala, R. (2015). A contemporary approach to validity arguments: a practical guide to Kane’s framework. Medical Education, 49, 560-575. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12678

⁴Lesterhuis, M., Bouwer, R., van Daal, T., Donche, V., & De Maeyer, S. (2022). Validity of comparative judgement scores: how assessors evaluate aspects of text quality when comparing argumentative texts. Frontiers in Education, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.823895